Types

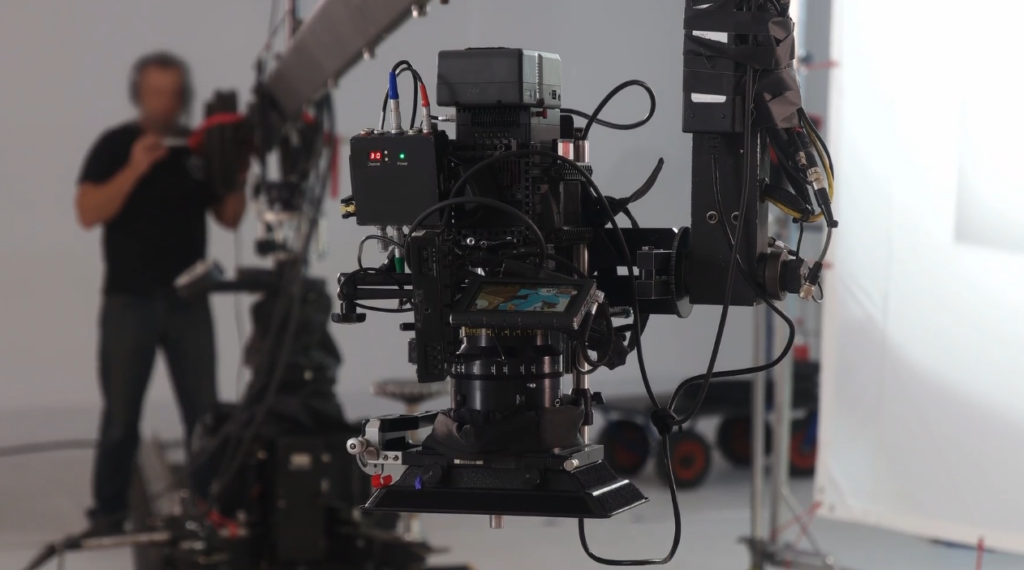

How, how fast, and where the camera moves determines the angles and shots it will produce. Camerawork includes both the aforementioned framing and the movement of camera which creates the illusion of depth (film is a two-dimensional photographic medium).

In terms of how stable the camera is and the kind of movement it engages in, there are the pan, tilt, dolly, crane, handheld, and Steadicam shots.

The camera could be mounted on a tripod at the desired height. The camera could move laterally from side to side while staying stable horizontally to achieve pan shots.

The camera could also pivot vertically, up and down, to create tilt shots.

The camera could be mounted on a mechanical arm to create crane shots that move freely through space, both horizontally and vertically. Crane shots provide an omniscient point of view.

When the camera moves smoothly on wheels, it creates dolly or tracking shots. With this setup, the camera can pull backwards to gradually reveal new information that is previously hidden from view in the frame. This is known as slow disclosure.

There are social implications of the slow pan and slow disclosure techniques. When the camera pans across, lingers on, or tilts upward over, a character’s body, it can make the character ominous. The camera movement can also appear leery, running the risk of objectifying the character. The camera replicates a gaze that eroticizes and dissects the body.

Just as lighting, Point-of-View (POV) shots, and faming that fragments female body parts turn a female character into a sexualized object, slow tilt also disassociates characters from real time in the narrative. The characters thus become floating signifiers that are ethereal, having no impact on or control of the space they inhabit. Slow pan or slow tilt also prolongs the amount of the time.

Source: Pexels

Examples

Watch this short video to discover outstanding camera movements that build up or subvert audience expectations. The camera needs not always show everything to tell a story. In some cases, the camera turns away to spare audiences from witness gruesome scenes. The short video outlines some key camera movements including the slow push in, the creep out, and distracting movements for plot development.

Invented by Garrett Brown in 1975, Steadicam is a brand of camera stabilizer. It is now commonly known as a filming technique. The wearable device isolates the camera from the operator’s movement and enables smooth shots. This technique is often used in chase scenes.

During the filming of the speeder bike chase scene in Richard Marquand’s 1983 Return of the Jedi, Brown walked through a forest with Steadicam. During filming, the camera ran only at one frame per second. When projected at 24 frames per second during screening, the sequence gives the illusion of flying through the air at high speed.

In Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 psychological horror film, The Shining, further innovations were made. The Steadicam was inverted to hold the camera barely above the floor.

Exercise

Your Turn: Analyze the camerawork, particularly the dolly-turned-crane shot, in the final scene of Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet (1996). How does the camera movement convey grief and the restoration of political order?

Your Turn Again: Another strategy to show tension is to juxtapose shots of various characters’ faces. As the stuttering Chorus (a tailor named Wabash, played by Mark Williams) in Shakespeare in Love (dir. John Madden, 1998) moves along in delivering the Prologue of Romeo and Juliet, his stammer gradually disappears and he gains confidence. Eventually he is able to finish reciting the speech in front of a packed house.

Answer Key:

Will and his fellow actors do not initially know that Wabash would overcome his stammer. The tailor of stage manager Philip Henslowe, Wabash wishes to act on stage for personal enjoyment even if it would jeopardize the production.

To heighten the tension, the film juxtaposes close-up shots of Wabash’s straining lips as he stutters on a thrust stage with medium shots of Will Shakespeare (Joseph Fiennes) wringing his hands backstage, the hands whence the play-text flows.

The uncomfortable silence and Wabash’s stuttering is accentuated by the audiences’ impatient sniggering as the camera—taking Wabash’s perspective—pans over the crowds in the pit and galleys that surround him in a multi-sided, three-tiered, open-air theatre with a central, uncovered yard.

Watch this scene and analyze how the framing, cuts, and shots work together to produce tension.

Further Reading

- Keating, Patrick. The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood. New York: Columbia University Press, 2019.