External and Internal Sounds

Definition

External sounds emerge from the film’s fictional world and are heard by the characters. In contrast, internal sounds represent a character’s private thoughts. Internal sounds can add depth to characters who may be misunderstood by other characters. In adaptations of classical literature, soliloquies (one talking to themselves) are often presented as internal sounds.

External sounds (including music) can reflect or provoke particular emotions and guide film audience responses to a scene. Internal sounds are usually more private and intimate. Film audiences have privileged access to everything, and a film’s sound design can create dramatic irony. Dramatic irony emerges when characters’ speech and/or musical soundtrack amplifies, or contradicts as the case may be, the mood of a scene.

Examples

Soliloquy as Internal Sound

In his Hamlet (1948), Laurence Olivier delivers the Danish prince’s famous “to be, or not to be” soliloquy in a unique combination of external and internal sounds while perched on a rock on the castle rampart. He speaks the lines and, later, presents other lines as voice over. On the soundtrack are music as well as sounds of lapping ocean waves.

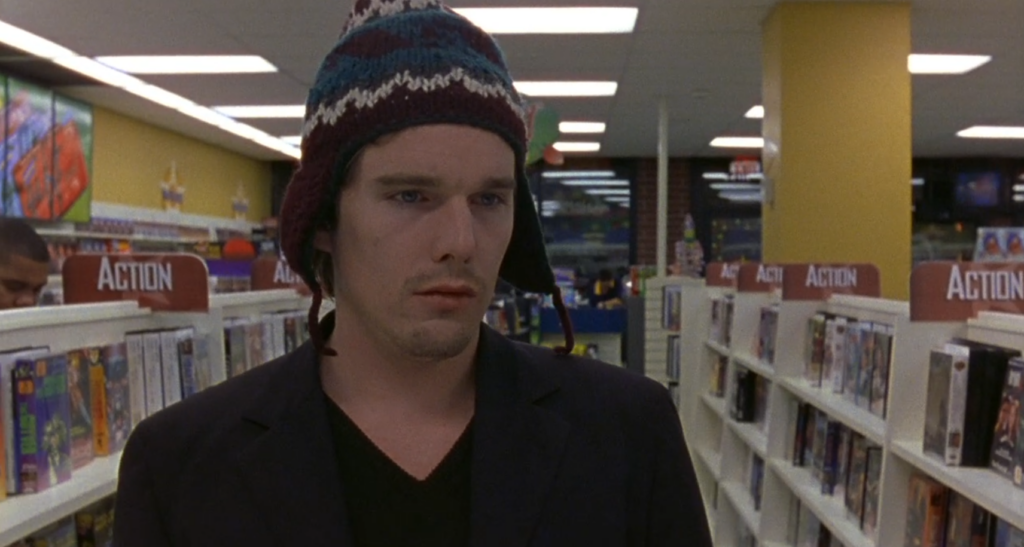

Michael Almereyda’s Hamlet (2000) features Ethan Hawke’s Hamlet contemplating his destiny as he strolls down an aisle in the film rental store Blockbuster in modern-day New York.

Hamlet’s “to be, or not to be” speech, as internal sound, parallels, not without irony, the external sounds in the store, including sounds and music from a nearby television set playing trailers of action flicks. The soliloquy focuses on non-action, while the action flicks seem to urge him to take some action.

Private Thoughts as Internal Sound

Internal sounds play a key role in the depiction of thought processes of Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) in James Cameron’s 2009 science fiction film Avatar. The following scene begins with Jake’s voice-over narration about his dreams, aspirations, and new outlook on life after suffering a spinal injury in war. He is paralyzed from waist down. He may face impairments but he refuses to allow them to disable him.

Internal sounds, in the form of Jake’s thoughts, keep the following scene afloat. Film audiences are granted access to Jake’s thought processes leading up to his tackling the bully in the bar, but other characters cannot hear the internal sounds of Jake.

Dramatic Irony: Internal vs External Sounds

Some films contrast internal and external sounds in ingenious ways to tell a story. The King’s Speech visualizes vocal disability through visceral, dual perspectives. It frames its protagonist Bertie’s disability in aural as well as visual terms.

The film’s central character, Bertie, who suffers from stuttering, does not believe any therapy can ameliorate his condition. During his first meeting with his speech therapist Lionel Logue, Logue asks Bertie to read a text aloud and assures him that he can read without stammering even before treatment begins. He ventures to record Bertie’s speech on a Silvertone Home Voice Recorder—the latest technology of the time.

Bertie reluctantly gives in, only to be surprised when Logue puts headphones on his ears and plays music. The text in question turns out to be Hamlet’s ‘to be or not to be’ soliloquy. With music in the headphones, Bertie cannot hear himself, and the film puts the audience in his aural perspective as we hear the Overture from Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro on the soundtrack. Visually, however, the film audiences take Logue’s perspective. The gap between hearing and seeing is highlighted by the dual visual and aural perspectives. The Overture drowns out Bertie’s recitation.

Mozart becomes the internal sound for Bertie. Logue does not hear the music in Bertie’s headphone. Audiences, however, are put in Bertie’s aural perspective and hear the internal sound. The “to be or not to be” speech constitutes external sound, heard by both Logue and Bertie but not by film audiences!

Unable to hear himself, Bertie assumes he has humiliated himself again with his stammer and decides to end the session, but Logue persuades him to keep the record even if they will not meet again. There is, of course, always a twist. After more frustrations with his stuttering, Bertie eventually sits down to replay the disc but is pleasantly surprised to find that Logue is right. Bertie’s recitation of Hamlet turns out perfectly fluent.

More Dramatic Irony: The Audio Bubble

Internal sound, in the form of music a character listens to through her earphones, can seal the character off from the rest of a film’s fictional universe. She could be in her own bubble, oblivious of her surroundings. This could be set up to contrast external sounds that are audible to other characters.

One example of this type of “bubbles” can be found in Ang Lee‘s family drama film Eat Drink Man Woman (1994). Jia-zhen, the eldest daughter of Mr. Chu, is a devout Christian and a high school teacher in Taipei. In the following scene, she listens to psalms through her earphones while waiting for the bus after school. Ming-dao, her colleague, a football coach, rides up to her on a motorcycle to offer her a ride. However, Jia-zhen is drowned by the Christian music and is in her own world. It took her quite a while to realize that Ming-dao is talking to her.

As the aerial shot pans over the school’s yard, the external sound of students clamoring matches the shot. However, as the camera continues to pan, the ambient noise gives way to Christian hymns. The transcendental soundtrack seems incongruent with the shot at this point–until more information is revealed.

The scene cuts to an eye-level shot of Jia-zhen, earphones on and zoned out. The volume of the psalms increases and drowns out the external sounds. At this point it becomes clear that the psalms are not non-diegetic, incidental music to accentuate plot elements. This internal sound, music in Jia-zhen’s ears, now dominates the scene’s sonic landscape.

Let us watch the following clip before continuing with our analysis.

This is where humor arises. Ming-dao, on the motorcycle, is talking to Jia-zhen, yet his words are inaudible, because the film audiences are now placed in Jia-zhen’s aural and visual perspective. External sounds return only when the scene cuts to a shot of Jia-zhen, emerging from her blank stare. This is a shot over Ming-dao’s shoulder, and their conversation is now audible. A more subtle context here is that Ming-dao is interested in Jia-zhen romantically. The two eventually begin seeing each other despite this awkward encounter.

Exercise

Inaction versus action. Internal versus external sounds. Almereyda’s Hamlet plays with, and contrasts, these oppositional elements to add ironic distance to and a modern take of the clichéd soliloquy of “to be, or not to be.”

Your Turn: Watch the following scene twice. Analyze the use of, and contrast between, external and internal sounds, thought processes, and conflicting messages from the soliloquy and from the film trailers playing on the television set within this scene.

Further Reading

- Walker, Elsie. Understanding Sound Tracks Through Film Theory. Oxford University Press, 2015.