What is a Film?

“Cinema, movies, and magic have always been closely associated. The very earliest people who made film were magicians.”

– Francis Ford Coppola

Film as an art form is constituted by light, illusion of movement, and the manipulation of space and time. This section covers the basic vocabulary for film analysis.

Lighting

In film studies, lighting refers to the interplay between motion-picture light and shadow. Whether photographed on film or created on computers (CGI), lighting is a key component to give meanings to the images. The following photo shows a lighting crew working with a lamp and a lighting diffuser on a tripod.

Source: Pexels

Light illuminates the scenes and images. Light is also itself a formal element of cinematic art. Filmmakers use light to create mood, reveal or conceal characters, and establish the setting of a story.

Lighting can enhance or disguise the texture, depth of field, emotions, and mood of scene. The following photo shows the same actor under different light, with the left half of his face brightly lit and the right side of his face in dim light.

Source: Pexels

For example, strong contrasts between light and dark (shown below) draws audiences’ attention to visual details and evoke different moods. The same face could appear approachable or sinister depending on lighting choices.

In this video you will learn more about frequently used lighting techniques.

Topics covered in the video include:

- 1:04 Three-Point Lighting

- 4:00 High Key vs. Low Key Lighting

- 5:57 Soft vs. Hard Lighting

- 9:38 Naturalistic vs. Expressionist Lighting

Your Turn: Reflect on a film we are studying. How do light and shadow define the moods of a compelling scene?

Tip: Read more about lighting in this lesson unit.

Illusion of Movement

Films, also known as motion pictures, depend on an illusion of movement.

Analogue and Digital Projection

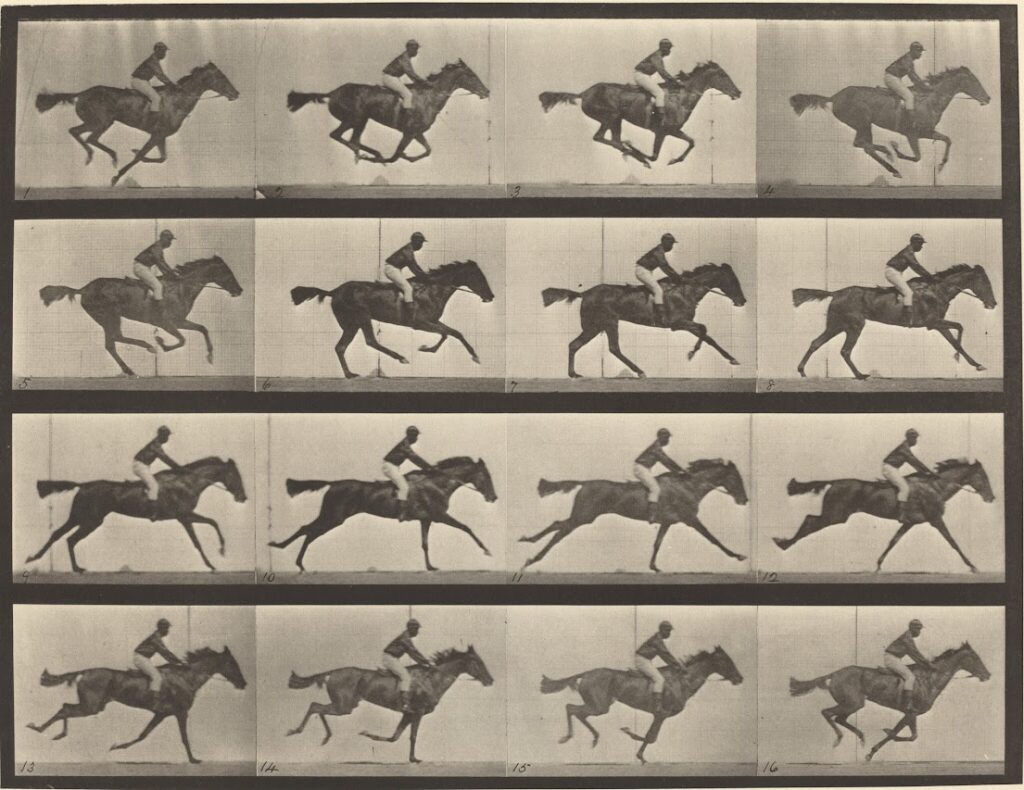

A film camera’s lens registers light and shadow on either film stock or a digital video sensor to create a series of pictures. Cinema projectors, television screen, or video monitors then transmit these pictures as illumination. The following photographs, when viewed as a series, depict a key element of motion pictures.

Racial Bias in Early Film History

Shot by Eadweard Muybridge at the University of Pennsylvania in 1884 and published in 1887, this famous series of sequential photographs depicts a rider and a horse in motion. Muybridge began photographing horses in 1873 on the farm of California governor and industrialist Leland Stanford. Muybridge used a device known as zoopraxiscope to put these photos in motion. Known as “Plate Number 626,” this plate is a forerunner of film as a medium.

It is notable that the photos show an unnamed Black jockey riding a horse. It is a sign of historical racial bias when the horse’s name, Annie G, is preserved, but we do not know the name of the jockey. The only other person of color featured in the photography collection was a mixed-race boxer named Ben Bailey.

What Is the Frame Rate?

The illusion of movement is created by showing, in quick succession, a series of still images with small variations (known as frames). When at least 24 images are projected per second (the frame rate), our eyes perceive fluid movements on screen.

This principle is explained in the opening scene of Steven Spielberg’s 2022 semi-autobiographical, meta-cinematic film The Fabelmans (a film about filmmaking). In the short clip below, the young Sammy Fabelman (Mateo Zoryan) is going to a movie for the first time and is scared. To reassure Sammy, his father Burt (Paul Dano), an engineer, explains to him how a cinematic projector works and how the 24 per second frame rate induces the optical illusion called the persistence of vision. In contrast, his mother, Mitzi (Michelle Williams), a pianist, takes an artistic approach to explain what a motion picture is: it is a dream!

High Frame Rate

More recently, some filmmakers used higher frame rates to produce sharper images. For instance, most of the scenes of Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert’s Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022) was shot at a high frame rate. This enables the post-production team to put any scene into slow motion if needs be.

Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit trilogy (2012–14) was shot and projected at 48 frames per second. Ang Lee used the rate of 120 for both Gemini Man (2019) and Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk (2016).

Film scholars often utilize visual and cultural studies methods to analyze not only “sequences” (such as a film’s opening sequence) and scenes (a self-contained narrative unit) but also, and especially, individual frames as meaning-generating images (film stills).

Your Turn: How is film similar to, and at the same time different from, the visual arts such as paintings?

Learn more about open and closed framing as well as the framing device in this lesson unit here.

Space and Time

While the sculptural art is primarily concerned with space and music unfolds in time, films have both temporal and spatial axes. Films manipulate time and space in a number of ways.

Camera movements (when the camera turns away or around) and angles can immerse viewers in a space, or jolt the film viewers out of a space and land them in a different space.

The camera can also move seamlessly from an outdoor space to an indoor space, putting film viewers in the characters’ perspectives.

The cinematic presentation of time (the temporal axis) is key to the spatial dimension of story-telling. A film’s narrative can fragment, compress, or fuse events occurring at different times, present objective or subjective perceptions of time passing.

Slow motion (an effect achieved by speeding up the camera, or shooting at a high frame rate) or freeze-frames (when a still image is shown for a period of time) would slow down time for film audiences to appreciate complex movements or to pay special attention to important scenes.

Read more about cinematography in these lesson units.

Let us take a look at an example.

Montage and slow-motion compress space and time in the masked ball scene in Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet (1996). Shots of Harold Perrineau’s Mercutio (Romeo’s best friend) in drag transitions seamlessly to other parts of the extravagant party, slow-motion, accelerated spinning, and cross-fading denote both the passing of time which is not depicted in real time on screen and the characters’ hallucinatory status (they take drug before crashing the party).

Conversely, intricately choreographed complex action scenes could be shot at a slower speed and be accelerated in post-production to generate the illusion of characters’ fluid yet precise moves.

In the “No Man’s Land” scene in Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman (2017), Gal Gadot’s Wonder Woman gains newfound powers.

This fight scene is presented with “ramped speed”—with fight sequences slowing down and speeding up within a single shot, as exemplified by this clip below.

Thus, films give temporal meanings (temporality) to cinematic space and location while endowing time with site-specific meanings (spatiality).

Film scholar Erwin Panofsky calls these phenomena the “spatialization of time” and the “dynamization of space.” The film viewer remains immobile in this dynamic process of the unfolding of space-time. Read Panofsky’s 1936 essay, “Style and Medium in the Motion Pictures,” on the website of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton.

Your Turn: Compare and contrast your experiences attending a stage play and a cinematic film. Consider the elements of space and time and your relationship to the action on stage and on screen.

Note that film and theatre do have a lot in common. Film works with the camera’s (film audiences’) mobile vantage point, while theatre works with its audiences’ fixed perspective. Many directors cross over the genres of film, theatre, musical, television, and opera, such as Julie Taymor and Danny Boyle.

A director and costume designer, Taymor is known for her 1997 Broadway hit The Lion King. She also directed such operas as The Magic Flute as such films as Frida and The Tempest.

Boyle directed Isles of Wonder, the opening ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics, as well as such films as Trainspotting, 28 Days Later, Sunshine, Slumdog Millionaire, Steve Jobs, and Yesterday.

Further Readings

- Bazin, André. What Is Cinema?, 2 vols. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967–1972

- Bolter, Jay David and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000.

- Bordwell, David. Poetics of Cinema. New York: Routledge, 2007. PDF online by the author.

- Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986.

- Eisenstein, Sergei. Beyond the Stars: The Memoirs of Sergei Eisenstein. London: BFI Publishing, 1995.

- Eisenstein, Sergei. “The Montage of Film Attractions” in Richard Taylor (ed.), Sergei Eisenstein Selected Works vol. I: Writings, 1922-1934. London: I.B. Tauris, 2010), pp. 39-59.

- Lumière, Auguste and Louis, Letters: Inventing the Cinema, ed. Jacques Rittaud-Hutinet. London: Faber and Faber, 1995.